By: Nantoo Banerjee

The government and the Reserve Bank may disagree, but the way the country’s trade deficits and external debt are rising it may be a matter of time before India goes for another IMF-World Bank bailout. The current indicators on the two counts are hardly comfortable. Take the debt position first. The total debt of the Indian government since the country’s independence till 2014, when the Modi government came to power, was Rs.55 lakh crore. Now, between 2014 and 2023, the total debt has gone up to Rs.155 lakh crore. The per capita debt in this short period under the Modi government increased from Rs.43,000 to Rs.1,09,000. In real terms, India’s per capita net national income (NNI), increased by only about 35 percent from Rs.72,805 in 2014-15 to Rs.98,118 in 2022-23. NNI is an indicator of the total economic activity in a country as defined by the OECD.

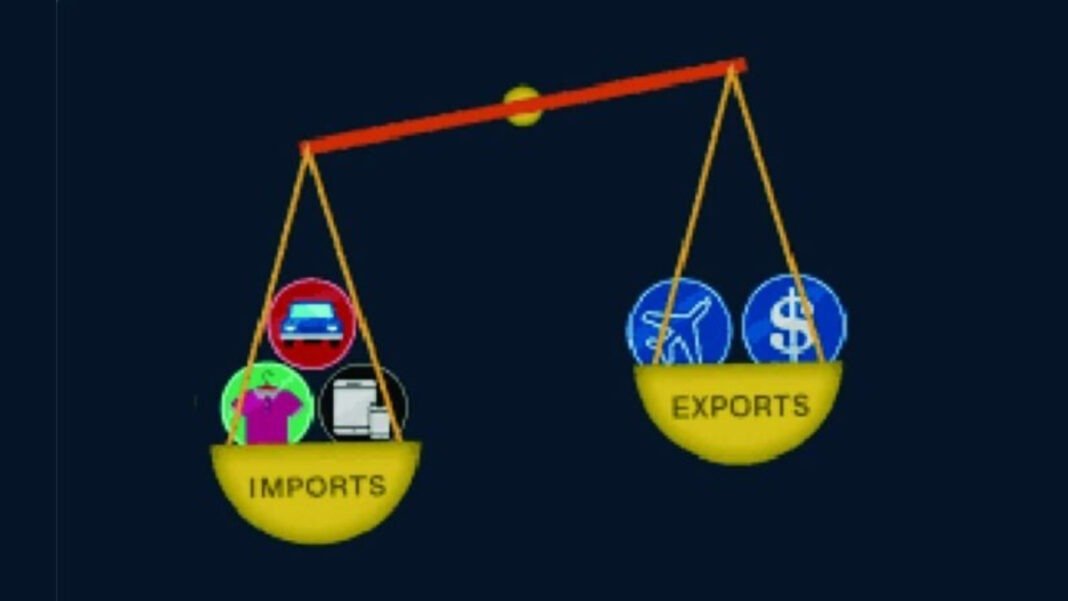

On paper, the debt situation right now may not look very alarming. The external debt is around 19 percent of the country’s GDP as against China’s 16 percent. Since 1995, China has been recording consistent trade surpluses. In 2022, China’s trade surplus surged 31 percent to US$876.91 billion, with exports rising seven percent and imports up only one percent. India’s domestic and foreign borrowings are constantly moving up. They get pumped up every year with a massive merchandise trade deficit. But for record remittances by Indians working outside and small surplus from services exports, the large merchandise trade deficit looks unsustainable in the long run. The Standard Chartered Bank expects India to post a balance of payment (BoP) deficit of US$24 billion in 2022-23 and $5.5 billion in 2023-24. This would be the first such instance in two decades when the country would log a BoP deficit for two years in a row. Remittances to India are close to $100 billion. Together, nearly 70 percent of remittances come from the US, UAE, UK, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar. The remittances and small surplus from the trade in services have been a continuous face saver.

However, risk factors remain. Another war in politically volatile West Asia, a job visa squeezes in the US and economic pressure in the UK can alter the inward remittances trend. A balanced trade or a small trade surplus should have been ideal for India. But, it is unlikely to come in the absence of a strong trade policy alongside the focus on raising domestic production. The country seems to have lost control over growing imports, especially from China, leading to growing trade deficits in goods. Possibly, India has forgotten its balance of payments (BoP) crisis of 1991. The BoP crisis was triggered by a combination of factors such as a high fiscal deficit, growing current account deficit, declining foreign reserves, and the Persian Gulf War. They led to a severe shortage of foreign exchange and made it difficult for India to pay for its imports and service its foreign debt. The government had to approach the IMF for a bailout package. Following this, it had to take a series of measures, including formal devaluation of Rupee, implementation of tight fiscal and monetary measures, and reduction of import tariffs, to address the crisis. The economy has since been stabilised and growing.

Few will disagree that the China factor changed India’s trade pattern. In April, 1991, India’s imports from China amounted to be worth only Rs.0.01 billion. In July, 2022, it reached Rs.814.38 billion. Two decades ago, China stood at the 10th position as India’s trading partner. Today, it stands No.1. India’s imports from China between 2001 and 2020 rose from US$2 billion to $95 billion. Today, the trade deficit with China has grown so large that it eats up the value of India’s almost entire inward remittances. The massive imports from China have severely curtailed job opportunities in India which is constantly under the pressure of unemployment. It’s hardly great news that for the last 15 years, India has consistently topped the chart of the largest remittance beneficiaries alongside mostly poor and job-starved nations.

Barring China and France, all major remittance receiving countries are comparatively poor countries faced with massive surplus labour such as India, Mexico, the Philippines, Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria. China and France receive remittances mostly through their project exports. Transfers of remittances are not a silver bullet for recipient nations. Economic research shows that over-reliance on remittances can cause a vicious cycle that doesn’t translate to consistent economic growth over time. Higher trade deficits lead to jobs being outsourced to foreign countries as more imports lead to fewer local job opportunities. Demand for imported goods leads to a decline in demand for locally made goods, which leads to the closing of factories and the associated job losses.

India’s import-based policies have resulted in uncompetitive exports and high consumer spending on imported goods. As long as India can pay for its imports, the country may witness more and more pressure on domestic production. It would look cheaper to purchase goods internationally than to produce them at home. Trade deficit potentially reduces the exchange rate of local currency. A country that has a trade deficit is sending a portion of its currency overseas. Trade deficit impacts a country’s GDP. It is one factor that is used to calculate a country’s GDP, a measure of the size of the economy. If the trade deficit increases, the GDP normally decreases.

It is difficult to understand why India has been overlooking the China factor, the single largest contributor to India’s trade deficit creating a growing pressure on unemployment, the purchasing power of Rupee and overseas debt. As per data shared by the Commerce Ministry in Lok Sabha, India’s trade deficit with China touched $71.56 billion in the first 10 months of 2022-23, just $1.7 billion short of the record high of $73.31 billion in 2021-22. The trade between India and China touched an all-time high of $135.98 billion in 2022. The chasm between India’s exports and imports with China grew wider in 2022 and continues to grow bigger. India’s export to China is small and dipping. The union commerce ministry’s provisional data showed India’s exports to China dipped by about 28 percent to $15.32 billion in 2022-23. The Modi government has clearly failed in its domestic manufacturing and foreign trade policies making the economy increasingly dependent on debt and imports. (IPA Service)