By: Dr Ratan Bhattacharjee

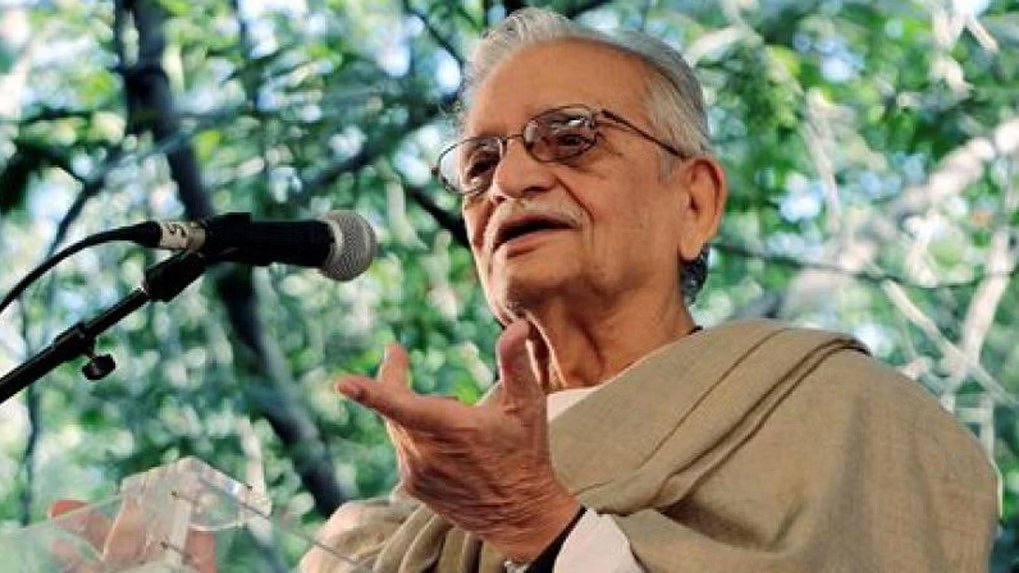

Gulzar once said, “My mother tongue is Punjabi, but my first language is Urdu, which was the case with people in undivided Punjab.” There is a certain comfort level in using one’s mother tongue. Nowadays, our children are interested in foreign languages, and they don’t realize that they may be missing out on certain connotations and emotional depth simply because they undervalue their mother tongue. Promoting native languages and making efforts to preserve them are essential in our times. Multilingualism contributes to the development of inclusive societies that allow multiple cultures, worldviews, and knowledge systems to coexist and cross-fertilize.

Tagore long ago described the mother tongue as ‘Mother’s milk.’ Like mother’s milk, the mother tongue also nourishes the health of our culture. Jhumpa Lahiri paradoxically regards her mother tongue, Bengali, as a foreign language and perceives a disjunction between Bengali and English. Sometimes, the mother language is a necessity, and Nobel laureates like CV Raman stressed that the mother tongue is the best medium for learning science. Raman emphasized the importance of teaching science in the mother tongue to ensure it doesn’t become an exclusive activity in which not everyone can participate.

In “The Fall of Language in the Age of English,” Minae Mizumura said, “I am a supporter of multilingualism, but multilingualism without a true understanding of universal language will only make us blind and ultimately ineffectual in realizing that very ideal.” This is particularly true in Assam and the whole of North-East, where multilingualism is indispensable for promoting a culture of inclusion and pluralism. India, including the Northeast, cannot ignore this culture despite slogans in favour of one nation, one religion. Attacks on plurality will only divide the country and destroy the cornerstone of our glorious heritage. That’s why even the UN promotes native languages worldwide. More than 40% of the world’s over 6,700 languages are threatened with extinction in the long term due to a lack of speakers. Languages, with their implications for identity, communication, social integration, education, and development, are of strategic importance for people and the planet. However, due to globalization, they are increasingly under threat or disappearing altogether. Every two weeks, a language disappears, taking with it an entire cultural and intellectual heritage. When languages fade, so does the world’s rich tapestry of cultural diversity. Contrary to previous beliefs, the state of Assam and its languages appeared more pluralistic after discovering 55 languages (including dialects) spoken by people in different parts of the state.

In Meghalaya, there are two main mother languages: Khasi and Garo, spoken by the people, and one called Jaintia. The Garo speakers, including Meghalaya and adjoining areas, comprise 575,000 people (according to the 1997 census). Some important dialects in this context include Matchi, Ruga, Ambeng, Atong, Matabengs, Akawe (also Awe), Chibok, Gara-Ganching, Duals, Chisak Megam (also known as Lyngngam), and Megam. Besides, the Achik dialect is said to be a predominant dialect among other intelligible dialects of Garo.

Assamese, spoken by more than 23 million people, is an Indo-Aryan language that evolved before the 7th century A.D. The Assamese language has been heavily influenced by several languages, including Ahom, Sylheti Bangla, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Rajbangsi, Maithili, and Rohingya. Other languages in Assam, such as Bodo, have been influenced by the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan language and are spoken by the Bodo community people and the native tribes of Tripura known as Kokborok. Dispur was declared the capital of Assam in 1973 when Shillong was carved out of Assam to become a part of the newly formed state of Meghalaya in 1972.

Khasi is the official language of Meghalaya and is spoken by about 900,000 people residing in Meghalaya. The Khasi language belongs to the Mon-Khmer family of the Austroasiatic society. It reflects the socio-cultural vitality of Meghalaya and is integral to its culture. Although English is the state language, the principal languages of Meghalaya are Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia. Pnar (Ka Ktien Pnar), also known as Jaintia, is an Austroasiatic language spoken in India and Bangladesh.

Nelson Mandela correctly said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.” Love for one’s mother language can lead to historic movements, as seen in Bangladesh. On 21st February 1952, when police opened fire on rallies, Abdus Salam, Abul Barkat, Rafiq Uddin Ahmed, Abdul Jabbar, and Shafiur Rahman died, with hundreds of others injured. This rare incident in history showcased people sacrificing their lives for their mother tongue. Unfortunately, people worldwide neglect their mother language, using career and global communication as an excuse. The states of West Bengal and Tripura in India celebrate 21 February as Language Movement Day. Assam also witnessed a long fight for the preservation of the Assamese language, which had a significant historical significance in the development of Assamese culture and heritage. In South India, there was a fierce movement against the imposition of Hindi, and people protested such efforts. For an Indian, English or any mainstream language can never exude the same emotional magic as our diverse mother languages.

Technology can provide new tools for protecting linguistic diversity. UNESCO is undertaking a great mission in 2023 by reminding the world of the need to safeguard indigenous languages. In India, more than 19,500 languages or dialects are spoken as mother tongues, according to census data. There are 121 languages spoken by 10,000 or more people in India, categorized into two parts: languages included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution (22 languages) and languages not included in the Eighth Schedule (99 languages). This linguistic diversity is true for many other countries. Oliver Wendell Holmes rightly said, “Language is the blood of the soul into which thoughts run and out of which they grow.”

The UN reports that globally, 40% of the population does not have access to education in a language they speak or understand. On one hand, this approach encourages the principle of inclusion, which is necessary for a diverse country like India, while on the other hand, it introduces education in the language that the learner masters the most and gradually incorporates other languages. As our global contexts rapidly change, it is crucial to revitalize disappearing or endangered languages. A child educated in their mother language’s fundamentals can easily progress to higher branches of learning. When a language is lost, it means the heritage of a nation is somehow lost. (The author is an International Visiting Faculty USA and a trilingual poet. He can be reached at profratanbhattacharjee@gmail.com)