By: Dipak Kurmi

The tribal movements in India have a history as ancient as other societal uprisings. The tribes, often perceived as rebellious, faced suppression by ‘civilized’ rulers equipped with standard quality arms. They found themselves entangled in conflicts with both Hindu feudal lords and British colonists, who encroached significantly on their indigenous rights and self-governing territories. According to Roy Burnan, alienation from land during British rule, caused by faulty legislation related to forest lands and goods taxes, along with a lack of understanding of tribal social organization (chieftain), led to numerous tribal uprisings. However, in later periods, the tribal movement has been marked by a strong tendency towards establishing tribal identity.

From 1763 to 1856, various regions in India grappled with the challenges posed by the Company Rule, giving rise to numerous rebellions. However, these uprisings, by their inherent nature, were not national but rather localized, reflecting their limited impact. Throughout the colonial period, tribal resistances and revolts erupted, yet a comprehensive analytical study examining these struggles, delineating the roles of specific sections and classes within the tribal population, leadership dynamics, local issues, mobilization, and revolt against British rule, is notably absent. The uprisings, with their distinct local issues and purposes, remained isolated from each other in different regions.

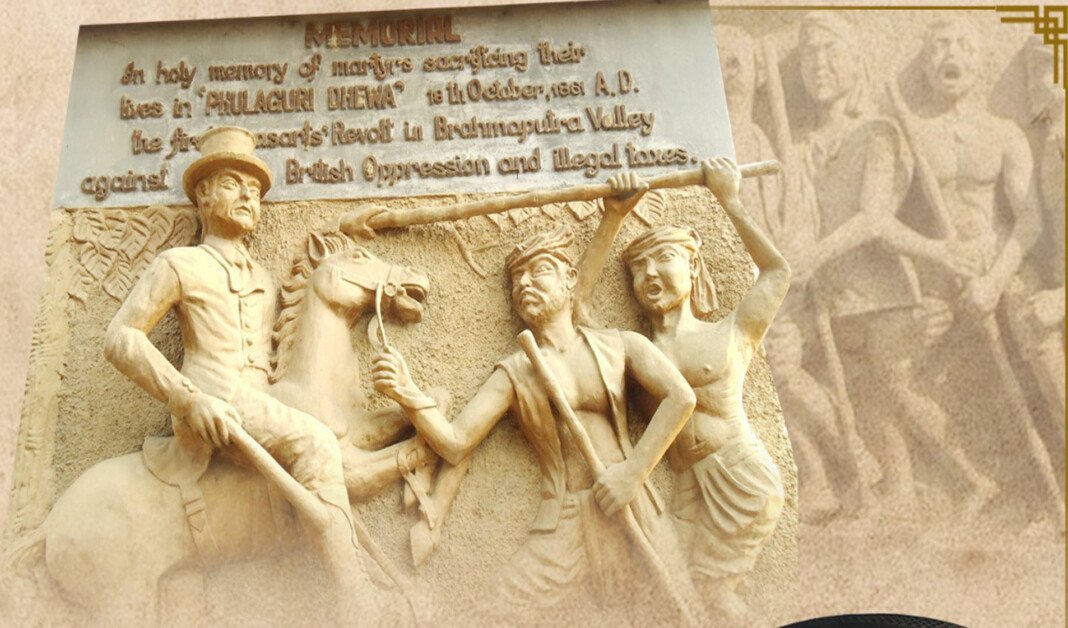

Unfortunately, the tribal resistance and revolt during the colonial period did not receive the deserved attention, despite its significant contribution to the dissolution of British rule in India. The nature of the struggle against the British underwent a transformation after 1860, marked by the imposition of taxes on land and productive goods. This imposition, challenging indigenous beliefs and traditions, was perceived by the tribal communities as a direct assault on their birthrights, leading to a spirited revolt against the British colonial authorities. The Phulaguri Dhawa stands out as a poignant episode—a battle of the peasants against the wrongs of British administration. This organized mass resistance, led by the heroic Lalung tribe, specifically in 1861, was a formidable response to the increasing tax burden and bureaucratic thoughtlessness imposed by the British rulers.

Approximately eighty-six tribal revolts unfolded in India, with around thirty-seven reported to have taken place in the North East region. The significant tribal resistance in this area left a substantial impact on British policy towards the tribal communities, as noted by Meeta Deka in 2011. Tribal movements in India, as ancient as other societal upheavals, are often perceived as rebellious, leading to suppression by ‘civilized’ rulers armed with standardized weaponry.

The tribal populace found themselves in conflicts with both Hindu overlords and British colonists, the latter encroaching significantly on their established customary rights and territories, as elucidated by M.S.A. Rao in 2012. Notably, the Phulaguri Dhawa emerged as the pioneering people’s and peasant revolt in the Brahmaputra valley, driven by a fervent desire for freedom from British administration. The leaders of this Dhawa, including Tiwa (Lalung) Raja Powali, played crucial roles as chieftains, as documented by A.J.M. Mills in 1984. In the year 1861, the predominantly tribal peasant population in the Phulaguri area, located in the Nowgong District, vehemently protested various issues, including the prohibition of poppy cultivation and the imposition of taxes on incomes, betel-nuts, and pan, as chronicled by K.N. Dutt in 1958.

The North East India, particularly Assam, has made significant contributions across various domains—socio-cultural, political, and economic—within the Indian Nation. However, much of these contributions have often gone unnoticed and unobserved by the national intelligentsia. A noteworthy example is the role played by Assam, especially the tribal community, specifically the Tiwa tribes, in the freedom movement of India. The Tiwa tribes, situated in middle Assam, played a substantial role much earlier than the Non-cooperation movement. In the quest to liberate the nation from the two-century-old British rule, the Tiwa tribes acted as major movers. The official records of the freedom movement highlight the organized uprising known as Phulaguri Dhawa, which took place on October 18, 1861. This event marked the first-ever organized peasant movement in the context of the Indian freedom movement, predating notable occurrences such as the Champaran led by Mahatma Gandhi and the revolt of Bengal farmers.

Hence, Phulaguri Dhawa (Tribal uprising) wasn’t merely a historic event; it was a profound expression of their sentiments. Additionally, it marked the inception of the first-ever non-cooperation movement within the Indian freedom struggle. Local tribal communities and peasants in Phulaguri actively appealed and ultimately decided to cease payment of taxes to the British administration. This unprecedented act had not been witnessed anywhere within Indian territory before the occurrence of Phulaguri Dhawa.

The Treaty of Yandaboo officially marked the conclusion of the Ahom Monarchy, establishing British Sovereignty in Assam. Following the British occupation, Assam underwent a division into two regions: Lower Assam and Upper Assam, with headquarters in Guwahati and Rangpur, respectively. David Scott assumed the role of Senior Commissioner for both Lower and Upper Assam, operating under the direct military rule of Colonel Richard, who served as the Junior Commissioner. David Scott’s responsibilities extended beyond mere commissioner duties; he also held authority over Civil and Criminal Justice and was tasked with revenue collection. Over time, the British expanded their sovereignty to encompass Raha and Kaliabar. Despite this, Sovereign Gobha continued to rule independently under Lalung (Tiwa) kingship until 1835. The British forcefully assumed control on March 15, 1835, led by Captain Lister, triggering continuous resistance from the Tiwas against perceived unjust British imperialism.

As per Hemkosh, the term “Dhawa” is synonymous with battle. Ganesh Senapati, a Tiwa researcher, asserts that the term finds its origin in the Tiwa word “Tawa,” signifying an encounter or battle. The Phulaguri Dhawa of 1861 in the Nowgong district of Assam was a localized agrarian uprising led by the Lalung tribe. India fell under direct British control following the end of the East India Company Rule in 1858. However, the British rulers persisted in their policy of exploiting peasants and their resources. The affluent middle-class peasant proprietors and government servants did not actively cooperate, being significantly affected by recent taxes on income, trade, and profession.

The year 1860 witnessed the prohibition of poppy cultivation, and the subsequent increase in land revenue on dry crop lands in 1861, particularly affecting the peasant economy in Nowgong. In September 1861, approximately 1,500 peasants peacefully marched to the district headquarters. The Magistrate consistently handled riots in a high-handed and provocative manner, denying entry even to their office compound. The Phulaguri locality on October 18, 1861, marked the initial instance of determined resistance by the Assam riots through the organization of Raij Mel (people’s assembly).

The British policy of 1860, prohibiting poppy cultivation, left the tribal areas entirely dependent on government opium. This prohibition disrupted the traditional domestic economy of these tribal regions, where opium consumption was estimated to be the highest in the province. Simultaneously, the introduction of the license tax, unforeseen by the local tribal population, raised alarms about the prospect of yet another impending tax. Rumors circulated that a new tax was to be imposed on their houses, barriers, and betel leaf cultivation.

Around 1,000 individuals had congregated by October 15, 1861, with 500-600 of them armed with bamboo lathis. A police party attempting to disperse the assembly was repelled, except for one policeman who was taken into custody by the people. By October 17, the gathering had swelled to 3,000 to 4,000 individuals. The police made another unsuccessful attempt to break up the assembly on the same day, arresting leaders, but they were all forcefully rescued by the people, forcing the police to retreat. Despite these events, the situation remained unchanged. On October 18, a British officer, Lieutenant Singer, arrived with a group of people and engaged with the leading members of the assembly. The rioters reiterated their complaints about the ban on opium cultivation and their dissatisfaction with income and pan taxes through a spokesperson. Expressing their frustration with the District Magistrate’s lack of interest in addressing their grievances, they contemplated taking their complaints to higher authorities in the mel. However, Singer ordered them to disperse and attempted to seize their bamboo lathis. In an accidental turn of events, British officer Singer lost his life during the revolt.

In response, the alarmed Nowgong District Magistrate personally came to the treasury and dispatched an armed force to the troubled spot. The armed force fired on the crowd, resulting in several deaths. By October 23, calm had been restored, with fresh military forces arriving from Tezpur and Gauhati. Narsingh Lalung and eight other tribal peasant leaders were sentenced to long-term imprisonment as a consequence of their involvement.

It’s crucial to note that the Panchaoraja (Five Kings, namely Sararaja, Khaigharia, Topakuchia, Barpujia, and Mikir raja) and Satoraja (Seven kings, namely Tetelia, Mayang, Baghara, Ghagua, Sukhnagog, Tarani Kalbari, and Damal) of the Lalung (Tiwa) kings, under their jurisdiction, actively participated and lent their support to the revolt against the British government administration, driven by their own grievances. However, the Phulaguri Dhawa tribal uprising was not a meticulously organized revolt; rather, it represented the culmination of numerous deep-rooted grievances of Lalung peasants against the British Government.

Unfortunately, colonial journalists tarnished the reputation of this uprising by portraying it as a revolt of opium eaters against the prohibition of poppy cultivation. Despite these misrepresentations, the Phulaguri tribal uprising holds immense significance, primarily because it marked the beginning of a new era of peasant awakening in Assam. This awakening continued with subsequent peasant uprisings in Rangiya, Lachima, and Pathorighat Ron. Although the Phulaguri uprising was essentially a tribal-led peasant revolt, it garnered support and sympathy from other segments of the peasant population. It served as evidence of the people’s desire to liberate themselves from the shackles of imperialistic exploitation. The decision of the tribal peasants in the Phulaguri locality to withhold taxes and reject government policies in 1861 should be considered as an early precursor to the non-cooperation movement in India.

In the latter part of October, General Henry Hopkinson, the Commissioner of Assam, arrived at Phulaguri with hundreds of sepoys and initiated a relentless campaign of torture in the Raha-Phulaguri region of Nagaon. Disturbed by the brutal atrocities inflicted upon their fellow people, the leaders of the uprising ultimately surrendered to the administration.

Subsequently, individuals such as Laxman Singh Senapati, Rangbar Deka, and Changbar Lalung faced the gallows in Nagaon Jail. Others, including Rupsingh Lalung, Sib Singh Lalung, Hebera Lalung, Nar Singh Lalung, Katia Lalung, and numerous comrades, were banished to Kalapani in the Andaman Islands due to their confession to the killing of Lieutenant Singer. The remaining leaders, including Narsingh Lalung and several tribal peasant figures, received harsh long-term imprisonment as the British Colonial authority ruthlessly quelled the Phulaguri Dhawa peasant movement.

The Phulaguri uprising on October 18, 1861, was rooted in local issues and demands, primarily confined to the Phulaguri, Raha, and other remote areas of the Nowgong district in Assam. This revolt had a limited scope, existing in a sporadic manner within a specific region. Unlike contemporary revolts that spread across various parts of India, the Phulaguri uprising did not achieve widespread momentum.

The failure of the revolt can be attributed to several factors. The absence of modern leadership capabilities, the lack of standard modern arms, and limited mass participation, particularly among educated proprietors, government servants, and the middle class, were significant challenges. Traditional methods of organization and techniques, coupled with economic constraints and communication barriers, further hindered the success of the revolt. Additionally, the lack of attention and acknowledgment from the intelligentsia about the significance of the revolt contributed to its ultimate failure in achieving its intended aims and objectives.

Upon careful observation and analysis, it becomes evident that the Lalung tribe actively organized and participated in a revolt against British government policies, driven by a sense of discontent. The peaceful and self-governed Lalung (Tiwa) community had long been considered a highly exploited social group since the colonial rule took hold.

The Lalung people adhered to their chief (Raja-Kingdom), customary laws, and traditions for the administration of their affairs. They preferred a tranquil existence marked by isolation, relying on the land and forests as primary sources of livelihood. However, it is noteworthy that the British administration showed a lack of specific attention and care towards their well-being during this period.

The tribal economy, integral to both local and national economies, played a crucial role. The imposition of new, irrelevant, and unfamiliar legal systems by the British administration proved to be beyond the capacity of the tribal communities. Consequently, the underprivileged Tiwa community found itself listed as a Scheduled Tribe under the new Constitution of India since 1950. In the present context, the Tiwa community is engaged in a struggle for survival, characterized by a strong tendency towards establishing tribal identity.

Phulaguri Dhawa wasn’t merely a tribal uprising; it stood as an anti-colonial movement embraced by the people. Despite falling short of its intended goals, the movement left an indelible mark, serving as a precedent that resonated with the populace and was soon followed by subsequent actions.

Regrettably, it saddens us to witness the negligence of both state and national governments in commemorating this significant event and honoring the martyrs. The administrations of free India, both at regional and national levels, seem to allocate little time or effort to organize even a brief function for the commemoration and celebration of this historic day.

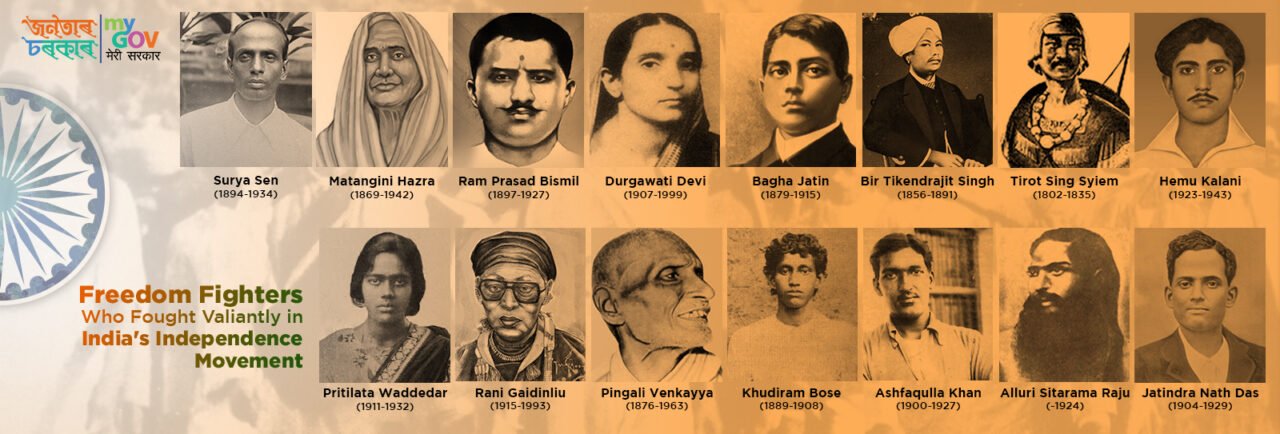

Nevertheless, the tribal resistance and revolt of Phulaguri played a pivotal role in inspiring people across the country to actively participate in various freedom movements, both during British rule and in the post-independence era. (The writer can be reached at dipaknewslive@gmail.com)