By: MR Lalu

Did Kantara the Rishab Shetty blockbuster take you into a rare multiplex marvel giving you a mysterious jolt? I have no words to address the unsophisticated beauty of the village life that the movie takes us through. Its religious intellectualism woven in the innocence of a bunch of forest-dwelling people took me back to my childhood. I witnessed it in the movie and was reminded of the impulses of spiritual powers that the non-Brahmin priest used to be obsessed with in a particular annual ritual at our local temple. The main attraction in the annual festival of the temple used to have a huge gathering determinately assembled to witness the morning padayani that went on for hours until the non-Brahmin priest, usually representing a scheduled caste community, breaking hundreds of coconuts and howling in all four directions with unclear sounds, normally known as his symbolic communion with the divine power. Throughout his spiritual exercise, the Oorali as he is called in Malayalam appears to be possessed by some supernatural powers and capable to predict matters that affect the temple and the village. Sometimes his prediction on theft inside the temple premises or anything of that kind used to get sorted out in public. His revelations were taken with rapturous attention and attracted the reverence of the upper caste Hindus and all devotees of the local deity without any speck of doubt.

Kerala’s socio-spiritual life is interconnected with various forms of rituals mostly dedicated to a pantheon of deities. A childhood without experiencing such rituals was rare in society and the emotion that a child grows up with would certainly contribute to his impulses further I, for all good reasons, have a non-judgmental view of Kantara, the movie that successfully took me through the domain of my childhood insistently taking my beliefs into a simmering point. I would rather call my movie experience a solid spiritual journey through the innocence and milder mannerisms of a village folk who came ready to revolt against a system that provoked their spiritual intentions and at a point of realization rediscover the real fantasy of spiritual incorruptibility by breaking barriers of the deceitful supremacy of a feudal mindset.

My village is known to have been protected by four divine guards in four directions. They are symbolically represented by four shivlings in the four corners of the village. And the temple situated at the center of the village is known to have been under the guardianship of these local deities and the belief system would resist you to be critical of anything that comes as part of the annual rituals. Obviously, the pattern of rituals and the buildup for the festivities may change from north to south of the state. Inevitably the essential meaning such rituals and celebrations come up with is the same and stands in unison with the protection of nature.

Sarpa Kavu or the abode of snakes or in common language, the sacred groves that the Kerala society protected in every village was considered as a pictogram of spiritual purity and ritualistic plurality symbolically maintaining the concept of amicable coexistence, a bridge that connected the essential spiritual oneness between men and nature. The rituals they performed were to please the divine forces which they recognized and believed would protect the entire village. Interestingly, all such divine elements are named in the lingua franca and their appearance and ritualistic expressions vary from place to place in different parts of Kerala.

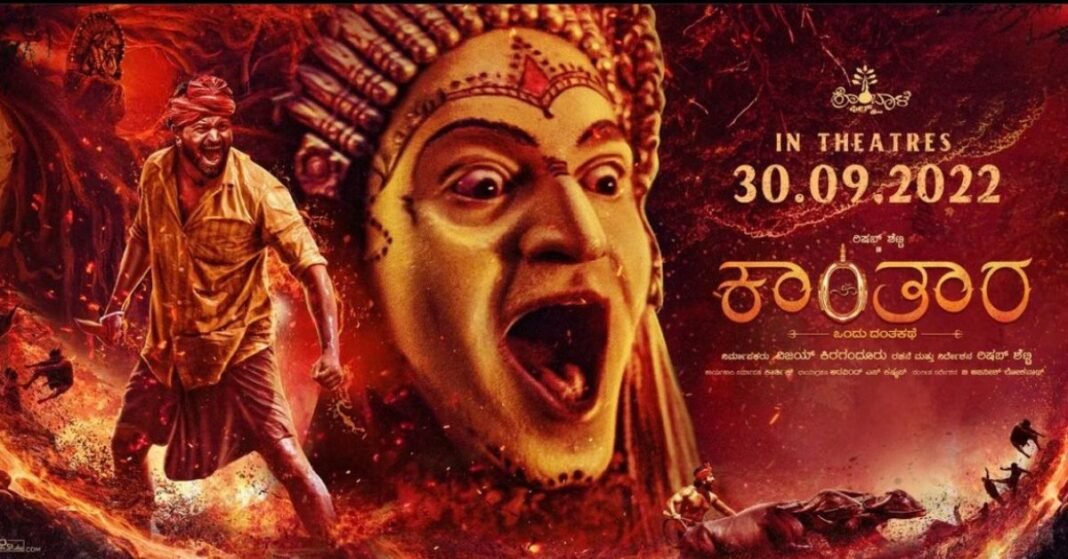

Kantara’s cinematic experience is an antique piece of visual luxury that is capable to press the viewer to his seat and with the surprise of his acting marvel Rishab Shetty, the all-in-one architect of the movie serves us a buffet of genuine acting in the platter of the socio-spiritual echo system of a society. Genuine research on the impact of the spiritual art form Kola in the life of a small bunch of people in their benign social setting is meticulously presented in the movie and the spiritual inclination that it is capable of ultimately creating in the viewer’s perception comes in the last ten minutes when the protagonist is taken over by a divine possession. A bone-chilling experience of artistic eloquence does not allow the viewer to leave the theatre without goosebumps of surprise and shock and there lies the earth-shattering climax of the movie.

The spiritual art form Kola which is the central theme of the movie is a Karnataka version of the Theyyam of Kerala. The Malabar region of the state is blessed with this Hindu ritualistic experience every year, especially in the districts of Kannur, Kozhikode, and Kasara God. Theyyam is performed by communities from the scheduled castes and tribes like Paravan, Pulayar, Malayan, Velan, and scores of other communities. Most of the villages are known to be protected by a grama devata or a village deity and the theyyam or kolam performed every year is a dedication to Bhagavathy, the divinity in the guard of the village. This must also be seen as spiritual art forms originated long before the advent of Semitic religions in India and they essentially pass and take us through the reverence that each society in this region held for the feminine form of divinity. Though Bhagavati, the female deity, is prominent in the theyyam art form, there are also many deities like Vettakkorumakan, Kathivanoor Veeran, Sree Muthappan, and many others representing the male pantheon of gods.

The Gulika Daiva played by Rishab Shetty in Kantara is the Gulikan in theyyam. The deity is believed to have come from the toes of Lord Shiva and was blessed with his divine powers. The Gulikan is also known to be the God of death. This theyyam is performed post-midnight in the sacred groves of Malabar by the Malaya community. The local folklore tells that Gulikan will be a secret companion or a divine presence throughout a person’s life witnessing all his karmas from his birth to death. Every single aspect of the village festival has a bearing on the societal well-being of the people. Depiction of divinity through these art forms stimulates the collective spiritual progress of society and leads its people to take strides in their pursuits for spiritual well-being.

Kantara as a movie has not only succeeded in helping the viewer touch the realm of magical realism but also a well-knit phantasmagoria of village life, fantasy, innocence, romance, and spiritual power and also established a deeper connection between the theme and the viewer’s spiritual cognizance. (The author is a freelance journalist cum social worker)