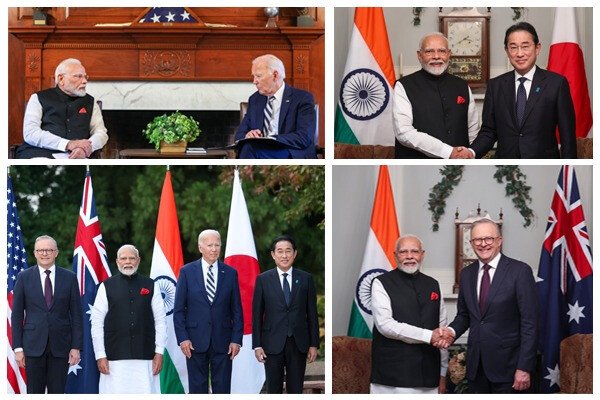

In the lead-up to the G20 summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had enthusiastically touted the event as a “people’s festival”, celebrating India’s G20 agenda with Bollywood flair. Yet, as the world’s spotlight turns toward India, international media has been increasingly critical of Modi’s leadership style on the global stage. According to recent research by the Pew Research Institute, a substantial 68 percent of polled Indians believe that India is “getting stronger”. However, this sentiment does not necessarily resonate with the rest of the G20 nations, including the United States, where no more than a third share this view. In fact, nearly half of respondents from other G20 countries feel that little has changed in terms of India’s global influence. While governments play a crucial role in shaping a nation’s image, it is essential to recognise that people and civil society institutions also contribute significantly. Official propaganda can sometimes be self-serving and ultimately unproductive. Take, for example, China’s situation, where despite growing unpopularity in the West at the government level, the country continues to attract more Western tourists and business than India. Public perceptions are just as vital as government-to-government relations, and sometimes even more so.

Unfortunately, the Modi government’s approach toward Pakistan and China has seen a deterioration in diplomatic relations, accompanied by a reduction in people-to-people contact. Apart from sporadic cricket matches that often resemble battles, there is minimal social interaction between Indian and Pakistani civil societies. This lack of social contact extends to tourism, cultural exchanges, and academic programs, not just with Pakistan but also with China. All three governments share the blame for this situation. However, it is in India’s national interest to encourage greater civil society contact across borders, especially with academia. Neighbours should be more open to each other’s media presence, which would foster understanding. Media can play a pivotal role in bridging gaps in perceptions. For instance, the Indian journalist Pallavi Aiyer’s book about life in China, though a decade old, stands as a testament to the power of such interactions. The absence of extensive media contact also explains India’s heavy reliance on Western perspectives when it comes to China.

While Indian society and culture maintain a certain appeal across much of Asia, including China, the same cannot always be said for Indian elite attitudes and prejudices. Indian elites are often seen as arrogant, pro-Western, and lacking in cultural and nationalistic spirit. This perception has led many in China to reach out to activists and intellectuals affiliated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in the past, favouring conversations in Hindi and Mandarin over English. However, recent shifts in Indian attitudes present challenges to a deeper understanding of its important neighbours. As India asserts itself on the global stage, it must not lose sight of the significance of people-to-people relations in shaping its image and diplomatic success. While governments engage in tough stances on national issues, encouraging civil society contact and cultural exchanges with neighbours, including Pakistan and China, is crucial. Such interactions can help bridge gaps, foster better understanding, and ensure that India’s global influence is not just a government claim but a reality acknowledged by the world. In the end, the strength of a nation lies not only in its leaders but also in its people and their connections with the world.