By: Mukul Bhowmick & Sangeeta Rege

In 2017, President Ram Nath Kovind stated that India was facing a “possible mental health epidemic” and asserted the need to provide accessible mental health services by 2022. Almost prophetically in India’s Union Budget for financial year [FY] 2022-23, mental health found a rare mention, even if it took us a pandemic to realize its significance. Many experts and stakeholders lauded the move, deeming it “gratifying”, “timely” and “much-needed”. But are the celebrations premature?

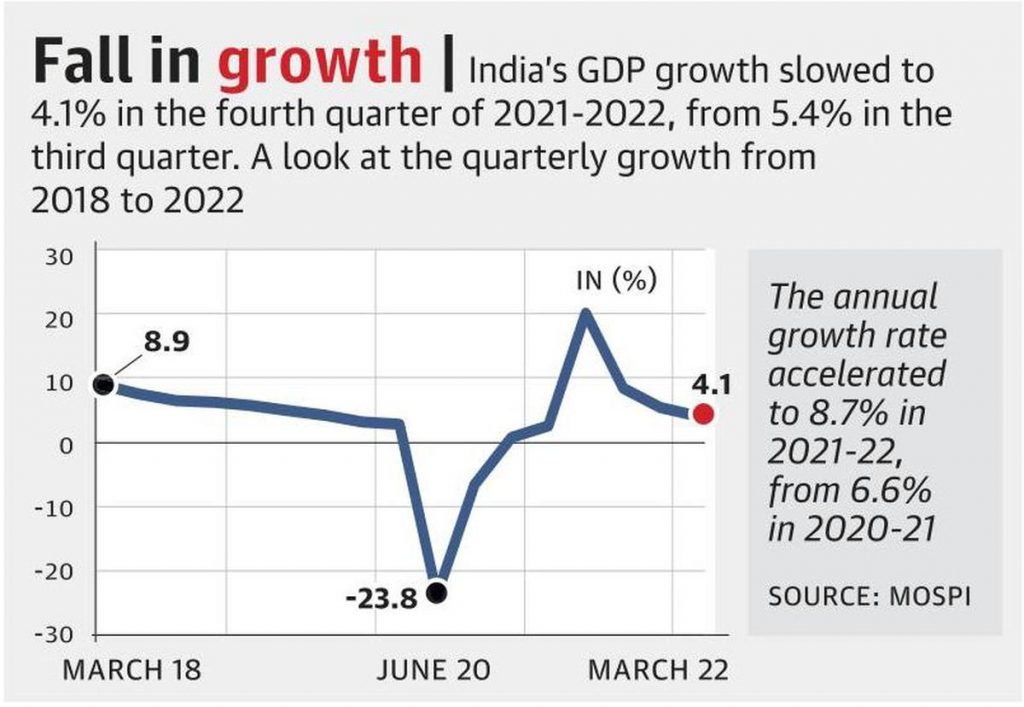

The Budget promises Rs 86,200.45 crores to the health sector for FY 2022-23, which amounts to 2 per cent of the total fiscal outlay. A total of Rs 670 crores is allocated to mental health, which is a 12.5 per cent increase from the previous financial year, although it amounts to only a 0.77 per cent of the total health budget. It is worth noting that 94 per cent of these funds are earmarked for two centrally funded institutes: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences [NIMHANS], Bengaluru (Rs 560 crores) and Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health, Tezpur (Rs 70 crores).

Furthermore, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman explained that “the pandemic accentuated mental health problems in people of all ages” and announced the launch of a National Tele Mental Health programme “to better the access to quality mental health counselling and care services”. The creation of a digital ecosystem for healthcare is fast gaining momentum in India’s public health policies and programmes. The proposed telemental health programme is in tune with India’s Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission [ABDM] launched in September 2021, aiming to provide accessible digital health services to Indians.

With the help of technical support from the Indian Institute of Information Technology-Bengaluru, 23 centres of excellence [CoEs] will be set up, with NIMHANS serving as the nodal centre. However, budget estimates for this new programme have not been disclosed.

The flagship initiative under the proposed programme is the nationwide Tele Mental Health Assistance and Nationally Actionable Plan through States (T-MANAS). A statement issued by NIMHANS detailed the vision of the initiative to ensure a comprehensive continuum of care for people in mental distress by providing immediate intervention and linking to in-person mental health services.

NIMHANS director Dr Prathima Murthy explained that the 23 CoEs are psychiatry departments from different states and union territories handpicked by the union government. These CoEs will essentially look after the running of the helpline in that state/region, including training of counsellors, monitoring and conducting operational research. In a diverse country like India, offering contextualized mental healthcare in local languages is a step in the right direction.

It must be noted that telemental health is a broad term referring to remote delivery of mental health services, including diagnosis, assessment, symptom tracking and treatment, by means of telephone, video calls or mobile-based applications. Its potential advantages include improved access to care for existing users of mental health services in underserved regions, reduced clinic-related infrastructure costs, and lower perceived stigma attached with visiting a mental health provider. This modality is of value in India, where the treatment gap for various mental disorders ranges from 28 to 83 per cent. The acceptability of such services is also evident in the surge in users resorting to telemental health, especially during the COVID-induced national lockdown. However, a detailed programme implementation plan has not been released yet. Will the helpline offer therapeutic services like counselling and psychotherapy? What are the guidelines to be operationalized for referral-related decision support systems? How will it ensure compliance in cases which require referral to healthcare facilities? Answers to these questions are crucial in determining effective implementation of the programme.

An abysmal dearth of mental health professionals poses a formidable challenge to the programme. According to the National Mental Health Survey (2016), the number of available psychiatrists in India ranged from 0.05 to 1.2 per lakh population. There is a paucity of clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers in absolute numbers, and a considerable variation in geographic distribution with a majority of mental health professionals concentrated in cities. In such a scenario, it is imperative to question – who will provide the tele-services? An already overburdened mental health workforce can hardly take on new responsibilities.

To combat this, there are plans to rope in ASHAs [Accredited Social Health Activists], ANMs [Auxiliary Nurse Midwives], and other community health workers in the telemental health programme for early identification of symptoms in rural and remote areas. Whether their responsibility will be restricted to creating awareness about the helpline or providing telecounselling is anyone’s guess. However, involving female frontline workers is an effort doomed to fail. Even before the pandemic, there is evidence to suggest they were overworked and underpaid, in addition to facing challenges like juggling domestic work and poor functionality of healthcare facilities.

A review of telemental health services based largely in the developed world asserts that outcomes of such services are comparable to in-person care, effective for a range of service-users and mental conditions. When it comes to resource-limited settings like India, however, we may not be able to generalize these findings. While a review of such services in low- and middle-income countries suggests positive outcomes for disorders like Alzheimer’s, dementia and depression, the evaluation uses standardized tests developed in the West with limited usage in the Indian context.

India hosts an array of mental health helplines run by state governments, civil society and non-profit organizations. There is a need for robust evaluation of such helplines before rolling out the new programme to ensure provision of evidence-based telemental healthcare.

The success of a telehealth programme is contingent upon a minimum requirement of access to mobile phones. According to data from the National Family Health Survey-5, Indian women’s ownership of a personal mobile phone averages at 54 per cent. However, there is a considerable rural-urban divide with only 46.6 per cent of rural women having a mobile phone that they themselves use.

It is safe to say that women from lower-income households are worse-off. To make matters worse, pervasive gender norms also act as barriers to women’s engagement with mobile phones. A 2018 study suggests mobile phones are seen as a potential risk to girls’ reputation before marriage and as a deterrent to fulfilment of domestic caregiving ‘duties’ after marriage. This renders women’s mobile phone usage vulnerable to constant surveillance by male relatives.

Yet another consideration is the protection of data privacy of the telemental health service users. Stigma related to mental health conditions and associated treatment seeking is widespread in India, and particularly greater when it comes to women. It serves as a major barrier to utilization of mental health services, and justifies all fears relating to breach of privacy. As seen in the case of antiretroviral treatment for HIV [human immunodeficiency virus], mandating personal identifiers like Aaadhar for telemental health services could lead to a drop in enrolment and service utilization.

Transgender persons, on the other hand, face a double whammy of the lack of valid documents needed to access public services as well as the absence of an effective legal framework to protect them from discrimination in case of any lapse in confidentiality. It is imperative to iron out the details of mental health data privacy in order to ensure their safe access to such tele-services.

India launched the National Mental Health Program [NMHP] in 1982 with an overarching goal of providing mental health care by utilizing the existing public health infrastructure. In order to scale this up, India inaugurated the District Mental Health Programme [DMHP] in 1996, decentralizing programme administration and implementation to the district-level. The main components of the programme include district-level activities like community engagement and outreach, and tertiary-care activities (Scheme A and B) like developing centres of excellence and institutional training of postgraduate students.

A paltry Rs 40 crores (or six per cent) of the total mental health budget are allocated to the NMHP, which only includes the tertiary-level Schemes A and B. This amount has remained unchanged from budget estimates from 2019. Furthermore, funds for the DMHP, the main service delivery component of the NMHP, are allocated through the flexible pool of non-communicable disease. In the absence of a clearly defined line-item for DMHP in the budget documents, the exact budget estimates cannot be ascertained.

Mental health does not operate in a social vacuum. Addressing social determinants of mental health like poverty, education and living conditions in our programs are just as essential as strengthening mental healthcare service delivery. The National Mental Health Policy (2014) enshrines principles of community mental health including mental health promotion, community engagement and intersectoral collaborations. The utility of community-based interventions through NGO-led projects like Atmiyata and Vishram, in improving mental health literacy, facilitating access to social welfare benefits, and reducing emotional distress and anxiety is well documented. However, the Union Budget offers little hope in giving fillip to such community-based interventions.

While technology undoubtedly offers a huge window of opportunity in improving public mental health, it must be accompanied by concurrent developments in the existing mental health infrastructure. Focusing on training primary care physicians in basic mental healthcare and creating a cadre of community mental health workers alone can ensure effective integration of mental health services in primary care. Efforts should be also be directed to creating awareness about recognition of signs of distress, suicide prevention and availability of mental health services in order to ensure uptake of the services.

In the context of the telemental health, it is crucial to build a diverse referral network, provide continued support, training the counsellors in comprehensive care, and being transparent about data collection and usage, in order to gain public confidence in the programme. The government should actively engage with other stakeholders working in this space and establish robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for future course corrections and improvements.

Any laxity in these efforts will possibly relegate the upcoming programme to just another helpline, in an ocean of many. (IPA Service)