By: Sanjay Roy

For the past three years India’s economy had to face the worst pandemic and Ukraine-Russia war which impacted global production and prices. These external shocks however only exacerbated the ailments that existed before the pandemic contributed by the unwary internal shocks of demonetisation and the imposition of the GST regime. The denial of the protracted impact of the pandemic and the consequent contraction of the economy required instead targeted strategies for revival of the eroded output and employment.

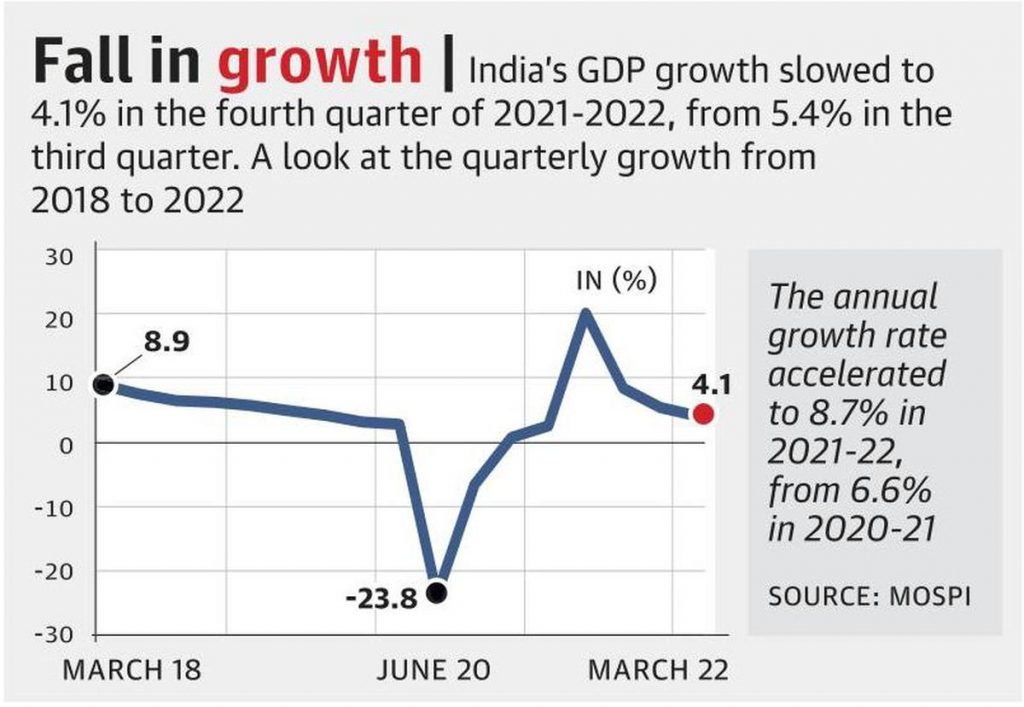

What seems to have overwhelmed the right concerns of the extraordinary situation were a wishy-washy stimulus and somewhat imprudent celebration of the recovery. In contrast to the rosy picture propagated through the media that the economy is recovering fast, the reality on the contrary indicates that we have a long way to go. The Indian economy is in the midst of slow growth, high inflation and high unemployment. On the top of that there has been depreciation of rupee and major out flow of capital to advanced economies and a debt overhang which is likely to increase with rising interest rates. The quarterly estimates of GDP figures released by the National Statistical Organisation on May 31, 2022; do not reflect an impressive recovery of the Indian economy.

In spite of the fact that we are still not out of the pandemic but the economic disruptions due to lockdown and initial supply bottlenecks eased out over time. According to the estimates India’s economy grew by 8.7 per cent in the financial year 2021-22, which appears to be impressive but has been calculated on the back of (-)6.6 percent contraction in the financial year 2020-21. In fact, in constant 2011-12 prices our GDP in the year 2019-20was Rs 145.16 lakh crores which has increased only to Rs 147.35 lakh crores in 2021-22. This essentially means that we have barely crossed the pre-pandemic levels after three years. Also the real GDP growth in quarter four over quarter three of 2021-22 records a growth rate of 6.7 per cent but the seasonally adjusted growth rate of real GDP during this period has been only 0.71 per cent. Noteworthy that the annual per capita GDP estimated in 2021-22 is Rs 1.07 lakh and that is still less than the Rs 1.08 lakh annual per capita GDP of 2019-20.

In terms of sectoral performance agriculture records a decline in growth rate from 3.3 per cent annual growth in 2020-21 to 3 per cent in 2021-22. In all other sectors the annual growth rates are higher than that of the previous year’s figures but with a caveat that annual growth figures do not actually portray the slowing down of the underlying recovery process. For instance, India’s manufacturing shows a growth of 9.9 per cent in the financial year 2021-22 which was (-) 0.6 per cent in the year before but if we compare quarterly figures on a year to year basis we see that in the fourth quarter of the 2021-22 financial year, manufacturing suffered a contraction once again of (-)0.2 percent compared to the fourth quarter of 2020-21.

Sometimes instead of growth rates measured in the backdrop of a contraction, absolute figures inconstant prices help us understand the extent of recovery. The manufacturing value added in 2019-20 was Rs 22.6lakh crores in 2011-12 prices which reached to only Rs 24.7 lakh crores inconstant price level in the financial year 2021-22. In case of construction there is hardly any revival although annual estimates of the 2021-22 shows a growth of 11.5 per cent. But if we compare the fourth quarter estimates of 2021-22 with the figures of the same quarter of a year before, the growth is only 2 per cent. In terms of absolute figures at constant prices the size of the construction sector value added in 2019-20 was Rs 10.4 lakh crores and after three years in constant 2011-12 prices the size of the sector stands at Rs 10.7 lakh crores in 2021-22. The other important sector within services ‘Trade-hotels, transport, communication and services related to broadcasting’ is yet to touch the pre-pandemic levels. In terms of annual growth rate figure this sector registers a growth of 11.1 per cent on the back of a contraction of (-) 20.2 per cent in 2020-21.

One can easily make out that the high growth registered in the 2021-22 is primarily because of the contracted base of the previous year. But if we see the absolute figures in constant (2011-12) prices this sector recorded a gross value added of Rs 26.9 lakh crores in the pre-pandemic financial year 2019-20. In the financial year 2021-22 at the same price level the gross value added of the sector reaches Rs 23.8 lakh crores which is still short of the pre-pandemic levels. For some sectors such as finance, insurance, real estate and business services the recovery has been fast may be because these are sectors which are less contact intensive and hence remained less affected by the pandemic. In fact, the stock market recovered much before the real economy picked up which simply reflects the fact that speculative gains hardly resonate with the state of the real economy. But what seems to be worrying is that the three sectors retail trade, construction and manufacturing together account for the major chunk of non-agricultural employment in India and the recovery in these sectors had not been encouraging.

The private final consumption expenditure which accounts roughly about 57 per cent of our GDP on the expenditure side is yet to recover from the perils of pandemic. Huge number of job loss and income cuts and also precautionary spending due to uncertainties and expectation of inflation in the future has consistently slowed down the growth of consumption expenditure. Comparing the annual figures of 2021-22 and 2020-21 the growth in consumption expenditure is 7.9 per cent. But the story does not end with annual figures.

In the first quarter of 2021-22 the growth rebounded from negative territory of (-) 6.0 per cent of the last quarter of 2020-21 to positive 14.4 per cent growth in the first quarter of 2021-22. This was due to the pent up demand accumulated during periods of lockdown and related disruptions in movements of goods and services. But in successive quarters the growth of consumption expenditure fell to 10.5 per cent in the second quarter followed by 7.4 per cent in the third quarter and finally to 1.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2021-22. This implies that the growth of private final consumption expenditure has slowed down even after the pandemic.

The real per capita annual private final consumption expenditure in India stood at 61.6 thousand rupees in 2019-20 in 2011-12 prices and after three years per capita private final consumption expenditure in 21-22 in constant prices has been less which is 61.2 thousand rupees. The other constituents in the expenditure side particularly Gross Fixed Capital Formation which indicates investments and accounts for 32.5 percent of GDP shows an annual growth of 15.8 per cent in 2021-22 compared to the previous year. But here also the growth of investment shows a consistent decline in each successive quarter. It is understandable that immediately after the lockdown all expenditures recorded a steep rise primarily because of a low contracted base and hence moderations are expected in periods that follow. But the moot point is we are still not back on the track in all respects of consumption, investments and production to the pre-pandemic levels.

Extraordinary shocks such as the pandemic or the war may have lasting impact on the economy. The World Economic Outlook April 2022 update revised its earlier forecasts of global growth downward by 0.8 percentage points and the downward revision is higher for developing countries compared to advanced economies. Moreover the inflationary trend is expected to continue for some time and the projected inflation rate is 8.7 per cent for emerging markets and developing economies. These extraordinary situations are expected to prompt the government in taking extraordinary steps to weather through the rough tides. And that could be nothing else but the redistribution of extraordinary profits made by the corporates during the pandemic in favour of those who face severe income loss during this period and that would revamp the dwindling demand. The other option is to use the pretext of an extraordinary situation to legitimize the increasing pains that the working people at large face.

It is amply clear now that the government has opted for the second path, together with carefully orchestrating debates, disputes and contestations in public discourse that flare up communal tensions and bulldoze the pains of the poor by the apparent jubilance of majority religious identity and the defeat of the minority ‘other’. (IPA Service)