By: M R Lalu

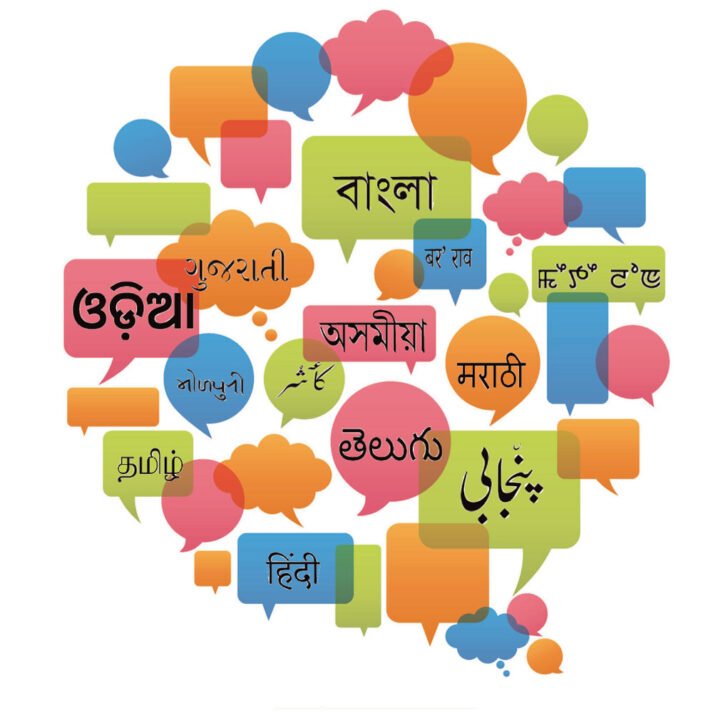

The Union Government’s push for ‘more focus’ on Hindi in the country has created much uproar as various opposition parties came out with their disagreements. The linguistic diversity that India is known for was feared to be in danger with the government’s move. The push for Hindi to be used as a link language was termed ‘Hindi imperialism’ by the opposition. This move, according to them, would create an emotional divide between the Hindi region and the non-Hindi-speaking areas. Linguistic Diversity has the beauty and power to essentially strengthen the area of communication and education that people from different backgrounds can conveniently choose from. Languages go back to the origin of civilizations. Existing in various forms, communication came to the collective consciousness of people and languages became the attire of thoughts and flourished across the globe. Traditions and practices are preserved in every society in their originality mostly encrypted in the language or dialect that they used for communication. The existence of ethnic societies was mainly based on the existence of their languages and with the death of the language, any society for that matter, falls into a state of oblivion, totally forgetful of their past. Many languages and dialects became extinct mainly due to their unjustifiably perceived notion of incompatibility in the eye of modern discourse. Colonial onslaughts on cultures were brutal by dominating the spirit of the cultural vitality of societies and dismantling their ethnic essence, invalidating and demonizing their power to fight and survive in a multilingual setup. India’s situation was not different. Though the country is witnessing a serious debate on Hindi being moved into a national framework of importance; the merit of the oldest language Sanskrit is almost a lost and forgotten affair. On a multidimensional analysis, Sanskrit is one of the languages that lost its credit and stature beyond imagination in its birthplace. Diversity being the essence of every society, multilingual and multicultural acceptance among societies strengthened them perceivably articulative on every difference that came in their way of congenial coexistence. Languages played their role to stitch differences into acceptance while finding common causes for shared interests to flourish.

Sanskrit is known to be the mother of all languages. Despite its being the most communicated language in ancient times, in India, it lost its glow as a language in a post-independent establishment. When languages united people across the globe, Sanskrit for various reasons could not flourish in India. With a large number of people choosing English as their spoken tongue, Indians have as much claim on it as any native speaker in America or England. The reach of Sanskrit as a medium of communication got limited among a handful of elite people in India, probably giving it the recognition of the language of the spiritual elite, the pundits. Away from the reach of the common man, Sanskrit is dying in India. There should not be boundaries in embracing languages as they are meant to break boundaries naturally and bring people closer. Interestingly, many books which are known to be not available in their original Sanskrit manuscripts are now available in Persian and many other European languages. Many vernaculars grew from the linguistic expression of Sanskrit and flourished gaining popularity, while Sanskrit depleted to the level of insignificance. Spirituality in India was defined and propagated in it but subsequently got sidelined as the essence of Bhakti or devotion got disseminated to the populace in local languages too. With its treasure of knowledge remaining heavy and probably inaccessible to the common man, spiritual texts from Sanskrit got translated into vernaculars helping the common man to delve deeper into them without being dependent on Sanskrit.

Research reveals the geographical influence of Sanskrit in various global languages. Most Asian languages are seen to be impacted by the influence of Sanskrit. Interestingly, countries like Germany have understood the intellectual and linguistic depth that Sanskrit holds and began to popularize the language in their universities. Iranians, Arabs and even the British found merit and power in Sanskrit and translated great classics into their languages. Governments in India kept away from initiatives to strengthen the mother of all languages for the fear that such a decision might topple India’s secular social engineering and invite the wrath of some sections. Schools adopting a three-language formula in their curriculum can teach Hindi, English, and an Indian language to the students. Many universities in the US teach Sanskrit as an Indo-European language. Interestingly, no language has a vocabulary as abundant as that of Sanskrit. To present an example, the English word ‘sun’ has 12 equivalents in Sanskrit. But English does not possess this vocabulary power and to fix this lacuna, it borrows new words from other languages including Sanskrit. An estimate says that of an approximate 6800 languages, about 200 languages in the world enjoy speakers more than a million each. The remaining languages have a meager number of speakers. With a huge number of people speaking it, Tamil enjoys a large acceptance in India and some other Asian countries.

With the National Education Policy coming into force, as part of its trilingual policy, states are authorized to take Sanskrit as a language through primary and secondary education. The policy is expected to bring a revamp in the education sector. India, a cultural diversity, despite its being a geographical unity, remained a single spiritual entity for ages as the language Sanskrit could bind the landscape through the spiritual aphorisms in texts that even today are monumental evidence of references that the world is appreciative about. The laxity with which the post-independent India treated Sanskrit was ruthless. To pursue Macaulayism, the idea of the English education system, we committed the biggest sin by burying the significance of the language of all languages. It was also due to the hypocritical secular track the country constitutionally decided to travel on, finding reasons to give Sanskrit a back seat. The fear of a probable backlash from the minority vote bank, if Sanskrit was favoured, was the main reason for the denial.

Societies with genetic, social, and linguistic diversities survive and flourish to their fullest potential, making intercultural assimilation of humanity, proclaiming the essential Indian Vedic idea of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam”, which means the world is one family. Indeed, Sanskrit is the only language in which we can find such thoughts of unparalleled ancient wisdom on universal brotherhood. Hypocrisy is what is the gesture of the Indian conscience these days. We carefully, in a surreptitious manner, killed a language that our ancestors cherished, nourished, and flourished with for generations. All credit as to why it is going to be extinct in this large subcontinent will come to us. Boundless knowledge is confined in books, unable to be perceived in its real sense as translations fail to give the real joy of reading the original texts. Cities like Haridwar and Rishikesh are known to be the seats of Sanskrit learning and research. Aspirants from across the globe flock to these cities to learn about Sanskrit. Mattur village of Shimoga in Karnataka is famous for its Sanskrit-speaking families. About 5000 residents of this village communicate in Sanskrit. More conscious efforts from various corners should be taken in the direction of reviving Sanskrit. The government has reasons to justify its move to lift Hindi to an elevated platform. But does it have reasons to not support a language that housed great cultural treasures for long? India should continue to survive as a multilingual entity with Sanskrit also finding a place to progress. (The author is a freelance journalist/social worker. He can be reached at mrlalu30@gmail.com)