By: M.R. Lalu

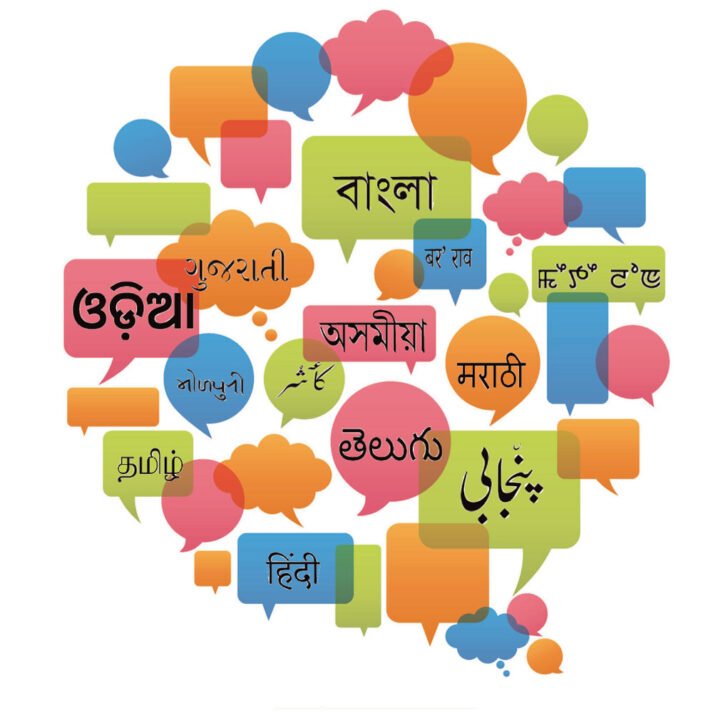

The central government’s recent push to elevate Hindi as a national language has triggered uproar once again. Multilingualism, with different cultural elements living in unison in a geographical space such as India, makes it the most exceptional social experience. Various languages and dialects that we preserved through generations make the essence of communication and they have been matchless in effect and content. Information technology’s enhanced versions underpinning the communication processes with adequate quality and clarity, it seems to be not necessary for a country like India to be battling for enforcing a particular language over the variety available. Multiplicity is the essential thread that a country such as India is intertwined into. When the globe is shrinking into a visible module accessible from anywhere, enabling people to jovially accept and appreciate the cultural variety that it offers, should there be an insistence on a linguistic enforcement growing into the level of a political compulsion. A country, which is a linguistic diversity, existing for years with a single civilizational essence has the societal ability to survive and go beyond political intimidation. The move by the government is not going to be an easy pass as reactions are streaming in from across the state borders.

The pomp and gaiety with which India celebrates its hundreds of festivals attracts the entire world. Festivals celebrated with the same significance probably in the same period or with little variation in different parts of the country with different names is the beauty of Indian ethnicity. Poila Baisakh in Bengal is Bihu in Assam and Vishu in Kerala. The same is Gudi Padwa in Maharashtra and Baisakhi in Punjab. These festivals share a common significance but are celebrated with local traditional flavours. The demand for nationalising Hindi in India is not new. Amit Shah stoked controversy through his tweet in 2019 in which he demanded that Hindi should become part of the Indian identity. As Hindi is widely spoken by a large population in the country, he reiterated to recognise it as the national language now. Much before in 2014, when the Modi government came to power for the first time, it had its directives given to the officers and employees of all ministries to use Hindi in their social media interventions. Linguistic inheritance is a sensitive issue in India. Especially the southern states which do not share a linguistic heritage in line with the Devanagari script and identify themselves with different language traditions are natural to resist the move. Tamil, one of the most ancient languages is an example. The Sangam literature, rich with philosophical aphorisms came to exist as early as 3000 BC. Hindi is relatively a younger brother to many classical languages in India with little contribution to the cultural eminence of the country. The last census depicts a clear picture of the linguistic propensities of Indians. According to it, about 56 percent Indians do not recognise Hindi as their first language. Nearly 44 percent Indians either speak Hindi or find the language comfortable for communication. When Hindi is dominant in some parts of the country, the remaining languages together take an upper hand resulting in a balancing act.

The influence of English in a British colony such as India must be repulsive to the cultural nationalism propagated by the BJP. Swami Vivekananda had a different opinion on this. Vivekananda, who spoke English throughout his world tour, was appreciated by his foreign audience for his in-depth knowledge, vocabulary and delivery in that language. He firmly believed that language could break barriers of territory and English, for him, was a medium of communication that he effectively used, to teach the world what India’s cultural tradition was. Nehru’s opinion on the choice of a national language was in line with what Gandhi viewed. He chose to believe that no country could become great based on a foreign language. He firmly believed that there should be consensus while choosing Hindi as India’s national language and he aptly rejected calling the demand of imposing Hindi on India as authoritarian. Both Gandhi and Nehru were of the opinion of having one Indian language being chosen as the national lingua-franca but they were aware of the complexity with which, at least in this case, the cultural linguistic diversity behaved. Political parties in Tamil Nadu have already registered their disagreement. The Congress party, with no special subject to unleash its attack on the government has come out against the ‘Hindi move’. As of now Hindi is not the national language. The more the BJP harps on the elevation of the language the more complex the situation becomes. We cannot but accept the circumstance that is emerging in different states. Large numbers of workers migrating from the northeast, Bihar and West Bengal into the state of Kerala have created a sudden urgency among the malayalis to learn and speak Hindi. Interestingly, workers from northeast, including those from Assam and Bengal conveniently communicate in Hindi with the Malayalis. The state, welcoming the employee influx, is helping the migrants with boards and hoardings in Hindi. I personally find an openness in the state with regard to its acceptance of Hindi as a language of communication with its ‘guest workers’ and an enthusiasm in learning it. But the state may not acknowledge an imposition.

The Constitution provides each state the right to choose its own official language. A particular local language, deeply engraved into the collective cultural history of a particular state, is natural to move against the national language indicator. It is interesting to note that almost everybody from the northeast is multilingual. A person from Arunachal Pradesh can speak his local dialect along with Hindi, English, Assamese and Nepali. This is real with many other states in the northeast. But in the southern states the situation changes. Except for the cities, most of the villages go solo with their mother tongue. Challenging the country’s nationalistic essence and hammering on India’s diverse linguistic ethnicities, Rahul Gandhi’s quip in the parliament calling India a conglomeration of states was an indication as to what would be the stand of the parties, if the government goes on trying to enforce anything in the direction of its dreamy cultural nationalism. History of agitations for linguistic identity in India should remind us of our national life that proclaims that there is no language that can hold us together as a nation. If there is anything that holds us one, that is the essence of Indianness. The geographical ethnicity that we have been pulsating through for years, cementing the essence of being Indian with all its plurality flourishing across linguistic borders should remain intact. (The author is a freelance journalist/social worker & can be reached at mrlalu30@gmail.com)